Tom's Camping Journal

The Jefferson River Canoe Trip

Monday May 14 - Monday May 21, 2001

The two bald eagles flew out of their nest high in the cottonwood tree, circled low and clacked their beaks in alarm, telling us bluntly that we were trespassing on their territory. We circled wide around the tree as we continued our exploration. This was truly an amazing place, packed with wildlife, where the whitetail deer seemed to bound out from behind every thicket. There were ducks and geese in the swamps, sandhill cranes in the nearby fields, wild turkeys in the willow thickets, blue herons nesting in the trees, and song birds everywhere: mourning doves, yellow warblers, and tree swallows, plus downy woodpeckers and magpies. We were on the river for only an hour before we found this site and paddled into the slough to get out and look around. We ended up staying there for the rest of the day and night.

My companions on this trip were Andy, almost eighteen, and his mother Pat. Andy wrote to me from a ranch in eastern Montana a few weeks earlier. Although he lives in California, he chose to take a year off from school to try some other things before graduating from high-school. For the last three months he worked as a hired hand on the ranch, helping out with sheep and cows, plus burning fields and fencing. I was immediately impressed by his writing, and thought to myself, "Here is a person who is good at organizing his thoughts and knows how to make things happen." Before long I was corresponding with his mom, working out the details of the trip. I warned them both that this would be a "survival trip", without tents, sleeping bags, or blankets. We would endeavor to make ourselves comfortable, but being cold and miserable part of the time would be a definite possibility. I think that Pat looked forward to the break from her work and the opportunity to spend quality time with her son. It was evident that neither of them were intimidated by my description of the trip. I picked them up at the airport the day before the trip began.

My companions on this trip were Andy, almost eighteen, and his mother Pat. Andy wrote to me from a ranch in eastern Montana a few weeks earlier. Although he lives in California, he chose to take a year off from school to try some other things before graduating from high-school. For the last three months he worked as a hired hand on the ranch, helping out with sheep and cows, plus burning fields and fencing. I was immediately impressed by his writing, and thought to myself, "Here is a person who is good at organizing his thoughts and knows how to make things happen." Before long I was corresponding with his mom, working out the details of the trip. I warned them both that this would be a "survival trip", without tents, sleeping bags, or blankets. We would endeavor to make ourselves comfortable, but being cold and miserable part of the time would be a definite possibility. I think that Pat looked forward to the break from her work and the opportunity to spend quality time with her son. It was evident that neither of them were intimidated by my description of the trip. I picked them up at the airport the day before the trip began.

We put the canoe into the Beaverhead River in the town of Twin Bridges, here in southwestern Montana. The Beaverhead joins with the Bighole River a few miles downstream to become the Jefferson River. It was my intent to start the trip late enough to take advantage of morel mushrooms and tree mushrooms, but early enough to avoid the high and dangerous waters of flood season. We started a week later than I originally planned, but that worked out just fine. In our second year of drought here, there simply isn't enough snow pack in the mountains to flood the rivers anyway. In fact, the water level was absolutely ideal for this kind of a trip.

These rivers are wide and shallow enough that there are always places where the canoe drags across the rocks on the bottom. Through much of the summer it is more a matter of walking a boat down the river than floating it. This time there was enough water spilling down those shallow riffles to turn them into moderately swift and very fun rapids. There were absolutely no mosquitoes.

In the Jefferson there are also many deep holes, great for swimming... when it is a little bit warmer out. The most dangerous part of the river are the many downed cottonwood trees that have the potential to suck under a boat or raft and its crew. People die that way every year, even with life jackets on. They get sucked in under a tree, then stuck against a branch so they cannot come up on the other side. Andy and Pat had considerable experience with canoes already, and I was glad for that in the upper sections of the river where the water was swifter and the fallen trees more numerous. If the river was much higher then I would have called off the trip as too dangerous. There is a fine line between not quite enough and way too much!

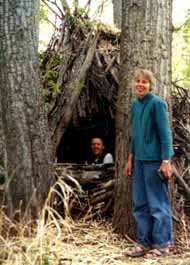

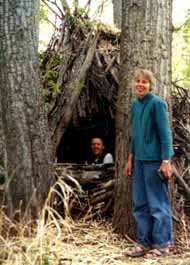

We expected rain on this first evening of the trip, so we built a small wickiup with its back turned against the weather and the lee side open to our campfire. The clouds rolled by the wind blew in gentle gusts, but the rain never came. Still, it was nice to have a cozy shelter out of the breeze.

Pat later gave me permission to use excerps from a letter to her friends and family, where she wrote: "Andy and I just returned from an 8-day Wilderness Survival canoe trip down the Jefferson River in Montana. It was an experience! We were cold, we were wet, we were hungry, and it was good! We were also warm, well-fed and dry. The weather was beautiful most of the time, though pretty cold and windy on some days."

For our first dinner we ate pigeon. They were not hard to catch... since they were pets. I started raising pigeons many years ago for meat, but never managed to create a sustainable system. They liked to perch on the roof of our house and nested on the ridgepole, crapping all over the porch swing below. After we adopted our children they in turn adopted the pigeons as pets. The kids wouldn't let me eat the birds any more. Felicia wanted to raise racing pigeons for awhile, so we built a cage for the birds in the chickenhouse to prevent them from getting out and roosting on the house. That helped, but once in a while the door got left open and it would take me weeks to catch them all again, to return them to the cage. We tried hauling the pigeons with us on vacation to set them free a hundred miles from home, but most of them still found their way back. Finally we ate a bunch of them in a primitive cooking class one time, sparing only the kids' favorite birds, at least for awhile. Eventually though, the kids moved on to horses and other pets, so no one was left to take care of the remaining pigeons. Besides, we wanted to use the cage as a brooder house to raise chicks. I packed the last six pigeons into a box (except for the two still nesting on our house) and loaded them live onto the canoe. We butchered five at camp, and one got away, minus a few tail feathers. My blunder.

For our first dinner we ate pigeon. They were not hard to catch... since they were pets. I started raising pigeons many years ago for meat, but never managed to create a sustainable system. They liked to perch on the roof of our house and nested on the ridgepole, crapping all over the porch swing below. After we adopted our children they in turn adopted the pigeons as pets. The kids wouldn't let me eat the birds any more. Felicia wanted to raise racing pigeons for awhile, so we built a cage for the birds in the chickenhouse to prevent them from getting out and roosting on the house. That helped, but once in a while the door got left open and it would take me weeks to catch them all again, to return them to the cage. We tried hauling the pigeons with us on vacation to set them free a hundred miles from home, but most of them still found their way back. Finally we ate a bunch of them in a primitive cooking class one time, sparing only the kids' favorite birds, at least for awhile. Eventually though, the kids moved on to horses and other pets, so no one was left to take care of the remaining pigeons. Besides, we wanted to use the cage as a brooder house to raise chicks. I packed the last six pigeons into a box (except for the two still nesting on our house) and loaded them live onto the canoe. We butchered five at camp, and one got away, minus a few tail feathers. My blunder.

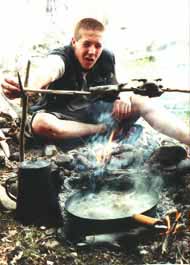

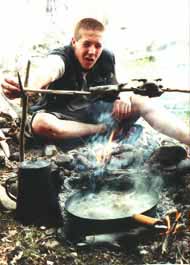

Andy helped with the butchering. It was evident that he has done similar work before. Most people are totally grossed out by blood and guts the first time they butcher something, especially if they have romanticized the idea as part of "living in harmony with nature". The reality is kind of messy, but Andy jumped right into the job. He is also quite the gourmet cook. He brought his own multi-spice container with compartments for eight different spices. No matter what we cooked, he spiced it up just right with salt and pepper, cayenne, curry, paprika and more. He was completely distraught when he realized he was out of garlic salt.

He roasted two of the pigeons over the fire. The others we cooked in a stew with some onions, tree mushrooms, and "Jerusalem artichokes" or "sun tubers" brought from home. We added tender young cattail leaves to the stew and boiled nettle greens in a separate pot. I warned Andy that these were older pigeons, guaranteed to be tough. He ate some, but seemed clearly disappointed that it wasn't more tender. Pat is a lifelong vegetarian, though she did not object to our feathered meal. She left all the meat for us. I thought it was delicious, even the pigeons.

The night was very warm, at least for Montana in May. We slept on grass padding in the wickiup, and stoked the fire intermittently to stay warm. Sleeping around a fire like that can be hard at first, but after a night or two a person grows used to it, or just plain tired enough, to be able to sleep comfortably from then on.

Cool air seeping in the back of the shelter seemed to flow right through my wool sweater until I buckled on my life jacket for extra warmth. I wore the life jacket to bed most nights after that. That made me feel like I was prepared for anything! We disassembled the shelter before leaving in the morning. Then we moved many miles down river.

Cool air seeping in the back of the shelter seemed to flow right through my wool sweater until I buckled on my life jacket for extra warmth. I wore the life jacket to bed most nights after that. That made me feel like I was prepared for anything! We disassembled the shelter before leaving in the morning. Then we moved many miles down river.

The Jefferson River wanders through farm lands and passes by several small communities. In places where the river is narrow and deeper, the cottonwoods are fewer and the developments tend to encroach more on the banks. We needed to get past these sections and back into the wild country where the river is more channeled, with sloughs and swamps and cottonwoods for wildlife habitat. Along the way we saw many pelicans, lots of beaver cuttings, more deer, and a river otter! I've only seen one other river otter in my life.

In past canoe trips on the Green River in Utah or the Upper Missouri Wild & Scenic River in central Montana, the water moved so slow that we had to paddle to get any where at all. On the Jefferson, however, the river moves fast enough that we usually only needed to paddle for steering purposes. It was truly amazing to pass down river so quickly with so little effort! We floated nearly thirty miles to the "Parrot Castle" fishing access, and still had time to build a shelter and make dinner before dark. The only obstacle was a very dangerous diversion dam built across the river to direct water into an irrigation ditch. We had to get out and portage all our gear out and around the dam. Good thing we didn't have much gear!

I don't know where the name Parrot Castle came from, unless it has to do with the rock formations, also known as "Point of Rocks" beside the river. The river bumps up against the Tobacco Root Mountains here, and it is the only spot where you can get from the public right-of-way in the river up to the public lands in the mountains, without crossing private lands in between.

A few years ago a stone mason spent some time here developing a small hot springs beside the river. The stone masonry is very nicely done, and the pool has a cold inlet to adjust the water temperature, plus drains to flush out the entire pool. It is a very nice hot springs, except for one thing. With easy access by road, the place has become a party spot and there is trash everywhere. We felt awkward walking around all the trash while doing nothing about it, but we just didn't want to take in with us in the canoe. My kids and I pick up trash every where we go, and I expect to bring them by for a camping trip shortly, so I guess we can work on it then.

A few years ago a stone mason spent some time here developing a small hot springs beside the river. The stone masonry is very nicely done, and the pool has a cold inlet to adjust the water temperature, plus drains to flush out the entire pool. It is a very nice hot springs, except for one thing. With easy access by road, the place has become a party spot and there is trash everywhere. We felt awkward walking around all the trash while doing nothing about it, but we just didn't want to take in with us in the canoe. My kids and I pick up trash every where we go, and I expect to bring them by for a camping trip shortly, so I guess we can work on it then.

On the first day of the trip, I made a quick bowdrill set and started the fire, then told Andy and Pat that I expected them to start the rest of the fires for the trip. This was Andy's day to learn the skill. He worked at the fire for some time, while I gave him room to experiment. Intermittently I offered suggestions until he had the basic form down, but he was growing quickly frustrated and impatient with the process. The rock handsocket we found was especially awkward to work with. Finally, I helped steady his hand on the socket and applied the right amount of pressure so that he got a hot coal. This combination of experimentation followed by assisted pressure seems to be a very effective way to teach the bowdrill. On the receiving end, you can really get a sense of exactly how the bowdrill should function. It helped that Andy was especially adept at working with his hands. He started all of our fires after that, usually on the first try. On the last day of the trip, Pat decided she wanted to start a bowdrill fire too, and she did.

We dug three trenches on a sandy island beach, then warmed each trench with Andy's fire. I like building that kind of shelter on sand bars where there is little growing anyway, and the landscape is periodically rearranged by floods.

While waiting for the ground to warm, we cooked a stew of rice and lentils with roots and onions, mushrooms, and wild lettuce greens mixed in. I noticed that the fish were active and threw in a hook with a worm. In only a few minutes I had a nice brown trout, probably 12 - 14 inches long. Andy took a turn and caught another brown trout. We ate them both with dinner, excited that we might be able to catch many fish along this trip.

In her letter, Pat wrote: "We foraged for our meals, but also took rice, lentils and oatmeal along, and some trail mix too for our midday snack. We ate lots of mushrooms (tree mushrooms and morels); wild greens like mustard, nettles, prickly lettuce, wild onions, lily bulbs (not the poisonous kinds), flowers like violets; and a little wild game like trout and birds and other assorted other stuff (not me, I'm just too vegetarian!) Unfortunately, we all forgot to bring salt. Try to imagine a whole week without salt! Try to imagine lentils without salt!"

Later we covered our trench fires with sand, set down ponchos, then made a big haystack of dried grass for insulation. We strung a tarp over the pile to block air infiltration. Unfortunately we were a bit exposed to the road, so some of the party goers at the hotsprings gawked and yelled comments as they drove away in the near darkness. We waited until we had the place to ourselves, then took our own turn soaking in the hot water before turning in for the night. We nearly howled with pain when the hot water first hit all the cuts and scratches on our legs, but we let in a little cool water, and slowly adjusted to the heat. Now that was survival with style!

Through the night in our haystack shelter, I enjoyed the warm sand underneath me and imagined that Andy and Pat were enjoying the comfortable bed as much as I was. So I was disappointed in the morning to learn that Pat's side of the bed never warmed up that much and she was slightly cold all night. Andy was warm enough, but not all that comfortable. Through the trip we each had one night that was clearly our best night's sleep, but they were all different nights in different shelters. We must not have had enough firewood in Pat's coalbed, or maybe too much sand. She tried out my spot after I got up and noted that it was much more comfortable!

Later we covered our trench fires with sand, set down ponchos, then made a big haystack of dried grass for insulation. We strung a tarp over the pile to block air infiltration. Unfortunately we were a bit exposed to the road, so some of the party goers at the hotsprings gawked and yelled comments as they drove away in the near darkness. We waited until we had the place to ourselves, then took our own turn soaking in the hot water before turning in for the night. We nearly howled with pain when the hot water first hit all the cuts and scratches on our legs, but we let in a little cool water, and slowly adjusted to the heat. Now that was survival with style!

Through the night in our haystack shelter, I enjoyed the warm sand underneath me and imagined that Andy and Pat were enjoying the comfortable bed as much as I was. So I was disappointed in the morning to learn that Pat's side of the bed never warmed up that much and she was slightly cold all night. Andy was warm enough, but not all that comfortable. Through the trip we each had one night that was clearly our best night's sleep, but they were all different nights in different shelters. We must not have had enough firewood in Pat's coalbed, or maybe too much sand. She tried out my spot after I got up and noted that it was much more comfortable!

We spent half the day exploring the area, climbing the rocky hills nearby, digging wild onions and other greens, and picking rose hips for tea. Pat found a nice patch of morel mushrooms. Andy caught a big bull snake and held it for awhile before letting it go. We liked the place so much that we decided to stay longer, but in another location. We found a secluded spot and built a large and elaborate wickiup with space and height inside to have a fire. We ate ashcakes with refried beans for dinner, plus we ate a nice mess of greens and mushrooms. We slept around the fire and stoked it all night long. A weather front had just passed through, sucking away all the heat as it left. This was the coldest night of the trip so far. The wickiup still had a few air gaps down low, letting cold air into the sleeping area, so it was more 'adequate' than 'comfortable'. Outside, there was frost on the grass in the morning.

We spent half the day exploring the area, climbing the rocky hills nearby, digging wild onions and other greens, and picking rose hips for tea. Pat found a nice patch of morel mushrooms. Andy caught a big bull snake and held it for awhile before letting it go. We liked the place so much that we decided to stay longer, but in another location. We found a secluded spot and built a large and elaborate wickiup with space and height inside to have a fire. We ate ashcakes with refried beans for dinner, plus we ate a nice mess of greens and mushrooms. We slept around the fire and stoked it all night long. A weather front had just passed through, sucking away all the heat as it left. This was the coldest night of the trip so far. The wickiup still had a few air gaps down low, letting cold air into the sleeping area, so it was more 'adequate' than 'comfortable'. Outside, there was frost on the grass in the morning.

We decided to stay yet another night in the area and spent most of this fourth day hiking up in the Tobacco Root Mountains. It was nice to get up high and see the world from a new perspective. Andy asked about every plant we passed by, wondering if they were edible or not. Almost all of them were edible, but as Andy discovered, most of them don't taste very good. He is very expressive with his face when trying to spit out something that tastes awful!

One thing we found on our hike was a duck nest with nine eggs in it, hidden below a mountain mahogany shrub beside a rock. Those birds do strange things sometimes. On day one we found a duck egg sitting on a log by a pond. I think they just have to lay whether they have a nest or not. Later Andy found a single goose egg floating in a pond. Anyway, the nest we found was nearly a mile from the river or any other suitable water source for ducks. Momma duck would never be able to walk her ducklings to the water, or so it seems. I would like to ask a knowledgeable biologist about that sometime.

Later, as we sat perched up on the mountain overlooking the valley below, I began to wonder about the future of the Jefferson River. I am usually pretty good at leaving work and stress behind on these trips, and sometimes I almost forget that I have another life. But I found myself trying to think of ways to protect what is left of the Jefferson River.

Later, as we sat perched up on the mountain overlooking the valley below, I began to wonder about the future of the Jefferson River. I am usually pretty good at leaving work and stress behind on these trips, and sometimes I almost forget that I have another life. But I found myself trying to think of ways to protect what is left of the Jefferson River.

Other rivers that we have paddled were nearly lifeless compared to the Jefferson River. Those were rugged, remote and desert-like environments. They were "wild & scenic rivers" because the land was too harsh to sustain any prior human colonization. Unfortunately, the more biologically rich environments usually go unprotected because they are already settled.

Much of the Jefferson River is still rich and alive, but there are also large portions of it's banks stabilized with rip-rap, which kills the channeling that is necessary to germinate future cottonwood trees. There is also the problem of development encroaching on the river, with houses lining the banks. Everyone wants a piece of the river for themselves, and this kind of development is sucking the life out of it.

With the population exploding in southwest Montana, it is just a matter of time before the river is completely dead, when rafters will float down a rip-rapped channel between two rows of houses, under the watchful eyes of homeowners barbecuing hamburgers on their decks. Now is the time to do something, and I would love to see a ribbon of wilderness and wildlife habitat following the river from its start to it's end. It would be good for the river and good for all future generations of people to enjoy this not-so-remote, but very exciting river. I spent some time dreaming about the project, and added it to my lifelong "list of things to do". I tried not to dwell on it too much though. After all, this was my vacation!

Back at camp we added more debris to our wickiup to tighten up the holes. I saw a large rattlesnake and left it alone. Snakes are quite edible, but there isn't much meat on them, and there doesn't seem to be too many snakes left these days, so I don't like to kill them. We tried fishing again and again and again, but couldn't seem to catch any more fish. We ate yet another meal of rice and lentils and wild greens and mushrooms for dinner. Both the weather and our shelter were much warmer, causing Andy to wake up with a cheerful shout in the morning after his best night of sleep for the entire trip. He couldn't stand another mushroom though, which Pat and I put in every meal we cooked, so he took over and made us three great big, delicious omelets for breakfast, loaded with spices of course.

After three nights at this wonderful place, it was finally time to get back on the river. We packed up, soaked in the hot springs one last time, then paddled on down stream. We portaged around another diversion dam and by-passed several islands. One of the islands is about a mile long, and I would really like to spend some time there, but we were not quite ready to stop yet, so we floated on down to a smaller island before making camp on a big, sandy beach. At one point along the river there was a moose just standing there at the edge, watching us float by. Of course we saw more whitetail deer, Canadian geese, and pelicans at every turn in the river. Some of the geese had their goslings with them on the water. At times we felt entirely hot, yet a moment later we would be chilled to the bone. That is the nature of our weather in May.

In her letter Pat wrote: "The best part was cruising down the river in the canoe -- so quiet, so part of the environment. We saw a lot of beautiful wildlife -- an otter, a moose, beavers, coyote, white-tailed deer, mule deer, muskrats, Bald Eagles -- including 3 inhabited nests, osprey and their nests, sandhill cranes, many ducks and geese, lots of other birds, in fact the morning orchestra was so beautiful that I wished I brought a recorder along to take the sounds home with me. The big sky was a deep blue on most days, with puffy white clouds, cottonwood trees lining the river bank in many places, islands, peninsulas, places to explore."

In her letter Pat wrote: "The best part was cruising down the river in the canoe -- so quiet, so part of the environment. We saw a lot of beautiful wildlife -- an otter, a moose, beavers, coyote, white-tailed deer, mule deer, muskrats, Bald Eagles -- including 3 inhabited nests, osprey and their nests, sandhill cranes, many ducks and geese, lots of other birds, in fact the morning orchestra was so beautiful that I wished I brought a recorder along to take the sounds home with me. The big sky was a deep blue on most days, with puffy white clouds, cottonwood trees lining the river bank in many places, islands, peninsulas, places to explore."

We still had much of the day ahead of us when landed on the island, and it wasn't clear what we could or should do, so we focused on some primitive skills to pass the time. We did a lesson on cordage first, from dogbane and nettle fibers. Then we went for a walk and made toy atlatls with mullein stalks for spears. My cousin Mel showed me how to do that. Finally we were making simple stone tools out on the beach. We had an atlatl contest at camp before making dinner or our shelters, but we all came in last place.... none of us could hit the cardboard box!

For shelter we dug big trenches in the sand, almost grave-sized. Then we lit fires in the trenches to heat up the ground. After dark we covered over the hot coals with sand, then made a simple roof over the top. I usually use sticks for the roof of these pit shelters and cover the top with earth or sand, but there were not quite enough sticks around, so we just put a log on each side and suspended ponchos across the top to trap in the heat. This is ordinarily my favorite shelter. I like to sleep in the warm chamber, even without any grass for a blanket. At this site there wasn't enough grass for a blanket anyway.

Unfortunately, I really goofed on the shelter this time. It is important to use a stick framework to support the middle of the poncho so that any condensation will run to the sides before dripping down. We draped our ponchos down inward, so the condensation dripped right in the middle of the pits, and there was quite a bit of moisture in the sand we used. That wasn't so much of a problem in Pat and Andy's combined pit shelter, since the drip landed in between them. But in my shelter the drip landed right on me, and every time I almost fell asleep there was a sudden cold splash on my face!

Furthermore, I hesitated to put too much sand on the coal beds, since Pat's bed was too cold the last time around. So I did not put nearly enough sand on, and we all nearly cooked in our shelters when we rested, in between scraping handfuls of cool sand in from the outside.

Furthermore, I hesitated to put too much sand on the coal beds, since Pat's bed was too cold the last time around. So I did not put nearly enough sand on, and we all nearly cooked in our shelters when we rested, in between scraping handfuls of cool sand in from the outside.

I finally ripped half the roof off my pit shelter because of the annoying drip on my head, then scrunched down into the bottom half, sitting cross-legged for the rest of the night. I felt really bad by morning for creating such a miserable experience for everyone. I was quite surprised then that Pat slept in and didn't want to get out of bed because she was so incredibly comfortable! She especially enjoyed being mildly steamed all night long and said it did wonders for her skin.

In her letter she wrote: "We took no blankets or sleeping bags, and packed pretty lightly on clothes, though we prepared to layer for cold. Some nights we kept warm around a fire in a shelter, other nights we dug trenches in the ground, burned branches in them to make a thick bed of coals, then put the soil over it and slept on the warm ground. It was great when it worked, but one night we built into a sand bank, covered it with a tarp and turned it into a sauna! It did cool down, and when avoiding the drips it was pretty cozy. In fact, that was my best night of sleep!"

We had another long day ahead of us, so we filled in our pit shelters, ate left-overs for breakfast, and paddled on down river towards the community of Cardwell. As we paddled by the fishing access we found the most dreaded thing of all: a sign with my name on it in big letters.

In small print the sign said, "There's been a family emergency in Pat's family. Call home." Pat and Andy have experienced family tragedy before, in a way that few people could ever relate to. We hitch-hiked to the phone at the Cardwell community store to get the terrible news. We dialed Renee first and she told us there had been a death in the family, but she didn't know who. Renee had been a wreck for the last two days, trying to get this message to us.

Pat called home and learned that it had actually been a close friend of the family, a very kind eighty-five year old woman, Marie. Pat and Andy were saddened by the loss of their friend, but also relieved that it had been a natural death and not a tragic accident of someone else. Since the memorial service would not be until after their scheduled arrival home anyway, they decided to continue the canoe trip. Andy bought ramen noodles and some candy at the store to survive the rest of the journey. Back on the river they told me all about Marie and what a wonderful person she was.

We floated on down river past the Lewis & Clark Caverns State Park. There the river is squeezed between two small mountain ranges, creating a channel that cannot meander back and forth. Under those conditions it is almost impossible for cottonwoods to germinate, so this stretch of the river is mostly barren of habitat and resources.

The wind blew intermittently in sudden gusts, so that it was often chilly and sometimes nerve-wracking to travel downstream. We could never tell if the next gust might be so big that it would just blow us right over, or kick up waves high enough to swamp the canoe. We had to work to keep the canoe pointed down river. The load of dry grass we tied to the canoe for our next camp didn't help matters much, since the wind grabbed at it like a sail.

We paddled downstream to a site where I previously built a small wickiup and kept it for trips just like this one. It was nice to arrive in camp with a shelter already completed. We had some quiet time to ourselves to climb up in the hills, to sit and think and to admire the spring wildflowers. In the evening we added some of Andy's ramen noodles to our usual fare of rice and lentils, wild mushrooms and wild greens. He cooked up two other packs separately, just to have something different. Although the wind blew hard at times, the air was almost still inside the wickiup. Again we slept around the fire, stoking it now and then through the night to stay warm.

With morning came more weather, and it appeared for awhile that we were in for a big rain. We used our grass bedding to stuff the remaining cracks in the shelter for better water-proofing. All we got for moisture was a sleet storm so short that we could have counted the sleet that hit the ground. Still, the weather was cold and windy. We waited as long as we could before heading out.

Our next stop was a favorite hunting ground for me, a place where we hoped to get a rabbit, a porcupine, or some carp, or something. Slowly the day warmed up some and Pat read and wrote in her journal and napped, while us boys went out to kill something, anything really. We hunted and fished for hours, but still had nothing to show for our efforts but three little crawdads, which we saved and boiled later on when we arrived at camp.

Our last camp was on a small "island", or at least it was an island on the map, but by now the water level had fallen to the point where the channel was dry around one side. The driftwood pile made a convenient v-shaped shelter between two logs. We added more logs and built up a triangular "log cabin" but without any roof. We had a central fire pit plus separate coal beds under each of us as we slept around the fire. The night was cold, but we were sufficiently warm, at least when the fire was burning bright.

Pat wrote: "On our last night out we woke up to almost a half inch of ice on our water! We also woke up at 4:30AM, all too cold to sleep. So we stoked the campfire higher, got a little silly, pulled our ponchos around ourselves and dropped off again."

We had a final breakfast of ashcakes and oatmeal. The sky was perfectly blue and sunny and completely still. We were hot by nine in the morning when we were packed and ready to paddle the final stretch of the river down to Three Forks. I just couldn't believe it when the icy cold wind suddenly kicked up again, and I was especially under dressed for it, with just a T-shirt. We paddled the rest of the way just to stay warm and covered about eight miles in only a couple hours. It was a nice trip, but I was ready to be done! We stopped at my in-laws house by the river and called home for a ride. Pat expressed that how much she enjoyed just floating down the river worry free, and that she wished it wasn't over. Andy enjoyed the trip, but I think he was ready for a change in diet. I don't know if he will ever eat another mushroom. We finished with a nice meal at a restaurant to mark the official end of the trip.

In her letter Pat concluded: "For me, the whole week was a sort of Sabbath, a spiritual experience filled with a sense of God's presence in nature, a peace and calm away from my busy life -- no phones, no schedules or demands, not much planning ahead and no huge decisions. Time for thought, prayer, writing, and even a little reading. A chance to gain a new perspective, to see new possibilities in old cottonwood trees, to see the river's world from it's surface rather than from the highway, to see food in a weed -- a stinging one at that, a home in a driftwood pile, a friend in a stranger."

Go to Participating in Nature: Wilderness Survival and Primitive Living Skills

See also

Tom's Favorite Canoeing Books

Help create the

Jefferson River Canoe Trail

Return to the Primitive Living Skills Page

Primitive Living Skills

Primitive Living Skills

My companions on this trip were Andy, almost eighteen, and his mother Pat. Andy wrote to me from a ranch in eastern Montana a few weeks earlier. Although he lives in California, he chose to take a year off from school to try some other things before graduating from high-school. For the last three months he worked as a hired hand on the ranch, helping out with sheep and cows, plus burning fields and fencing. I was immediately impressed by his writing, and thought to myself, "Here is a person who is good at organizing his thoughts and knows how to make things happen." Before long I was corresponding with his mom, working out the details of the trip. I warned them both that this would be a "survival trip", without tents, sleeping bags, or blankets. We would endeavor to make ourselves comfortable, but being cold and miserable part of the time would be a definite possibility. I think that Pat looked forward to the break from her work and the opportunity to spend quality time with her son. It was evident that neither of them were intimidated by my description of the trip. I picked them up at the airport the day before the trip began.

My companions on this trip were Andy, almost eighteen, and his mother Pat. Andy wrote to me from a ranch in eastern Montana a few weeks earlier. Although he lives in California, he chose to take a year off from school to try some other things before graduating from high-school. For the last three months he worked as a hired hand on the ranch, helping out with sheep and cows, plus burning fields and fencing. I was immediately impressed by his writing, and thought to myself, "Here is a person who is good at organizing his thoughts and knows how to make things happen." Before long I was corresponding with his mom, working out the details of the trip. I warned them both that this would be a "survival trip", without tents, sleeping bags, or blankets. We would endeavor to make ourselves comfortable, but being cold and miserable part of the time would be a definite possibility. I think that Pat looked forward to the break from her work and the opportunity to spend quality time with her son. It was evident that neither of them were intimidated by my description of the trip. I picked them up at the airport the day before the trip began. For our first dinner we ate pigeon. They were not hard to catch... since they were pets. I started raising pigeons many years ago for meat, but never managed to create a sustainable system. They liked to perch on the roof of our house and nested on the ridgepole, crapping all over the porch swing below. After we adopted our children they in turn adopted the pigeons as pets. The kids wouldn't let me eat the birds any more. Felicia wanted to raise racing pigeons for awhile, so we built a cage for the birds in the chickenhouse to prevent them from getting out and roosting on the house. That helped, but once in a while the door got left open and it would take me weeks to catch them all again, to return them to the cage. We tried hauling the pigeons with us on vacation to set them free a hundred miles from home, but most of them still found their way back. Finally we ate a bunch of them in a primitive cooking class one time, sparing only the kids' favorite birds, at least for awhile. Eventually though, the kids moved on to horses and other pets, so no one was left to take care of the remaining pigeons. Besides, we wanted to use the cage as a brooder house to raise chicks. I packed the last six pigeons into a box (except for the two still nesting on our house) and loaded them live onto the canoe. We butchered five at camp, and one got away, minus a few tail feathers. My blunder.

For our first dinner we ate pigeon. They were not hard to catch... since they were pets. I started raising pigeons many years ago for meat, but never managed to create a sustainable system. They liked to perch on the roof of our house and nested on the ridgepole, crapping all over the porch swing below. After we adopted our children they in turn adopted the pigeons as pets. The kids wouldn't let me eat the birds any more. Felicia wanted to raise racing pigeons for awhile, so we built a cage for the birds in the chickenhouse to prevent them from getting out and roosting on the house. That helped, but once in a while the door got left open and it would take me weeks to catch them all again, to return them to the cage. We tried hauling the pigeons with us on vacation to set them free a hundred miles from home, but most of them still found their way back. Finally we ate a bunch of them in a primitive cooking class one time, sparing only the kids' favorite birds, at least for awhile. Eventually though, the kids moved on to horses and other pets, so no one was left to take care of the remaining pigeons. Besides, we wanted to use the cage as a brooder house to raise chicks. I packed the last six pigeons into a box (except for the two still nesting on our house) and loaded them live onto the canoe. We butchered five at camp, and one got away, minus a few tail feathers. My blunder. Cool air seeping in the back of the shelter seemed to flow right through my wool sweater until I buckled on my life jacket for extra warmth. I wore the life jacket to bed most nights after that. That made me feel like I was prepared for anything! We disassembled the shelter before leaving in the morning. Then we moved many miles down river.

Cool air seeping in the back of the shelter seemed to flow right through my wool sweater until I buckled on my life jacket for extra warmth. I wore the life jacket to bed most nights after that. That made me feel like I was prepared for anything! We disassembled the shelter before leaving in the morning. Then we moved many miles down river. A few years ago a stone mason spent some time here developing a small hot springs beside the river. The stone masonry is very nicely done, and the pool has a cold inlet to adjust the water temperature, plus drains to flush out the entire pool. It is a very nice hot springs, except for one thing. With easy access by road, the place has become a party spot and there is trash everywhere. We felt awkward walking around all the trash while doing nothing about it, but we just didn't want to take in with us in the canoe. My kids and I pick up trash every where we go, and I expect to bring them by for a camping trip shortly, so I guess we can work on it then.

A few years ago a stone mason spent some time here developing a small hot springs beside the river. The stone masonry is very nicely done, and the pool has a cold inlet to adjust the water temperature, plus drains to flush out the entire pool. It is a very nice hot springs, except for one thing. With easy access by road, the place has become a party spot and there is trash everywhere. We felt awkward walking around all the trash while doing nothing about it, but we just didn't want to take in with us in the canoe. My kids and I pick up trash every where we go, and I expect to bring them by for a camping trip shortly, so I guess we can work on it then.  Later we covered our trench fires with sand, set down ponchos, then made a big haystack of dried grass for insulation. We strung a tarp over the pile to block air infiltration. Unfortunately we were a bit exposed to the road, so some of the party goers at the hotsprings gawked and yelled comments as they drove away in the near darkness. We waited until we had the place to ourselves, then took our own turn soaking in the hot water before turning in for the night. We nearly howled with pain when the hot water first hit all the cuts and scratches on our legs, but we let in a little cool water, and slowly adjusted to the heat. Now that was survival with style!

Through the night in our haystack shelter, I enjoyed the warm sand underneath me and imagined that Andy and Pat were enjoying the comfortable bed as much as I was. So I was disappointed in the morning to learn that Pat's side of the bed never warmed up that much and she was slightly cold all night. Andy was warm enough, but not all that comfortable. Through the trip we each had one night that was clearly our best night's sleep, but they were all different nights in different shelters. We must not have had enough firewood in Pat's coalbed, or maybe too much sand. She tried out my spot after I got up and noted that it was much more comfortable!

Later we covered our trench fires with sand, set down ponchos, then made a big haystack of dried grass for insulation. We strung a tarp over the pile to block air infiltration. Unfortunately we were a bit exposed to the road, so some of the party goers at the hotsprings gawked and yelled comments as they drove away in the near darkness. We waited until we had the place to ourselves, then took our own turn soaking in the hot water before turning in for the night. We nearly howled with pain when the hot water first hit all the cuts and scratches on our legs, but we let in a little cool water, and slowly adjusted to the heat. Now that was survival with style!

Through the night in our haystack shelter, I enjoyed the warm sand underneath me and imagined that Andy and Pat were enjoying the comfortable bed as much as I was. So I was disappointed in the morning to learn that Pat's side of the bed never warmed up that much and she was slightly cold all night. Andy was warm enough, but not all that comfortable. Through the trip we each had one night that was clearly our best night's sleep, but they were all different nights in different shelters. We must not have had enough firewood in Pat's coalbed, or maybe too much sand. She tried out my spot after I got up and noted that it was much more comfortable! We spent half the day exploring the area, climbing the rocky hills nearby, digging wild onions and other greens, and picking rose hips for tea. Pat found a nice patch of morel mushrooms. Andy caught a big bull snake and held it for awhile before letting it go. We liked the place so much that we decided to stay longer, but in another location. We found a secluded spot and built a large and elaborate wickiup with space and height inside to have a fire. We ate ashcakes with refried beans for dinner, plus we ate a nice mess of greens and mushrooms. We slept around the fire and stoked it all night long. A weather front had just passed through, sucking away all the heat as it left. This was the coldest night of the trip so far. The wickiup still had a few air gaps down low, letting cold air into the sleeping area, so it was more 'adequate' than 'comfortable'. Outside, there was frost on the grass in the morning.

We spent half the day exploring the area, climbing the rocky hills nearby, digging wild onions and other greens, and picking rose hips for tea. Pat found a nice patch of morel mushrooms. Andy caught a big bull snake and held it for awhile before letting it go. We liked the place so much that we decided to stay longer, but in another location. We found a secluded spot and built a large and elaborate wickiup with space and height inside to have a fire. We ate ashcakes with refried beans for dinner, plus we ate a nice mess of greens and mushrooms. We slept around the fire and stoked it all night long. A weather front had just passed through, sucking away all the heat as it left. This was the coldest night of the trip so far. The wickiup still had a few air gaps down low, letting cold air into the sleeping area, so it was more 'adequate' than 'comfortable'. Outside, there was frost on the grass in the morning. Later, as we sat perched up on the mountain overlooking the valley below, I began to wonder about the future of the Jefferson River. I am usually pretty good at leaving work and stress behind on these trips, and sometimes I almost forget that I have another life. But I found myself trying to think of ways to protect what is left of the Jefferson River.

Later, as we sat perched up on the mountain overlooking the valley below, I began to wonder about the future of the Jefferson River. I am usually pretty good at leaving work and stress behind on these trips, and sometimes I almost forget that I have another life. But I found myself trying to think of ways to protect what is left of the Jefferson River.  In her letter Pat wrote: "The best part was cruising down the river in the canoe -- so quiet, so part of the environment. We saw a lot of beautiful wildlife -- an otter, a moose, beavers, coyote, white-tailed deer, mule deer, muskrats, Bald Eagles -- including 3 inhabited nests, osprey and their nests, sandhill cranes, many ducks and geese, lots of other birds, in fact the morning orchestra was so beautiful that I wished I brought a recorder along to take the sounds home with me. The big sky was a deep blue on most days, with puffy white clouds, cottonwood trees lining the river bank in many places, islands, peninsulas, places to explore."

In her letter Pat wrote: "The best part was cruising down the river in the canoe -- so quiet, so part of the environment. We saw a lot of beautiful wildlife -- an otter, a moose, beavers, coyote, white-tailed deer, mule deer, muskrats, Bald Eagles -- including 3 inhabited nests, osprey and their nests, sandhill cranes, many ducks and geese, lots of other birds, in fact the morning orchestra was so beautiful that I wished I brought a recorder along to take the sounds home with me. The big sky was a deep blue on most days, with puffy white clouds, cottonwood trees lining the river bank in many places, islands, peninsulas, places to explore." Furthermore, I hesitated to put too much sand on the coal beds, since Pat's bed was too cold the last time around. So I did not put nearly enough sand on, and we all nearly cooked in our shelters when we rested, in between scraping handfuls of cool sand in from the outside.

Furthermore, I hesitated to put too much sand on the coal beds, since Pat's bed was too cold the last time around. So I did not put nearly enough sand on, and we all nearly cooked in our shelters when we rested, in between scraping handfuls of cool sand in from the outside.