Tom and Richard's Excellent Camping Adventure

Low, High, Low-Over the Mountains to Pony we Go

Tuesday September 1st - Sunday September 6th 1998

The new road plowed right through my old campsite. Unsure of what to do, we set our packs down to explore this new system of narrow trails carved out of the rock piles. The rock piles are the remains of the Gold Rush. Men ripped up the virgin creek bed in the quest for precious metal, washing the solids through an over-sized sluice box. The tiny flecks of heavy metal sank to the bottom. The other ninety-nine percent of the material was waste. The dredging stole the soil from the land. All that remains now is heaps of rock, one pile after another, stretching nine miles down the stream. Ironically, the barren wasteland is also a wildlife sanctuary.

Dredging may have taken the gold from the land, but the spirit of life still flows there. The creek percolates through the old rock piles, sometimes completely disappearing under the rubble, but always bubbling back to the surface a short distance down stream. Innumerable swamps of cattails and willows are home to all kinds of wetlands wildlife: blue herons, sandhill cranes, ducks, beavers, muskrats, and rainbow trout. Despite being only a few hundred yards wide and right next to the highway, the area is a sanctuary because the rock piles keep people out. It is simply too difficult too get anywhere climbing up and down the rock piles, navigating around the marshes, or bush-whacking though the willows. The cottontail rabbits seem to know this. The coyotes, the whitetail and mule deer, and the moose know too. The animals are safely hidden, while a non-stop stream of motorists speed by on the highway, guided by lines on the road into baited tourist traps ahead.

The dredge piles truly look like a wasteland, and the crude roads through and around my campsite are only the latest endeavor to do something useful with the useless. The roads provide access for the purpose of picking and baling rocks to be sold for stone masonry work. The bundled rocks rest on pallets ready for shipping. The problem is that the roads give access to more people and ultimately compromise wildlife habitat. I think of this as my habitat too, and I add the gutted campsite to my life-long list of secret spots laid open by a bulldozer.

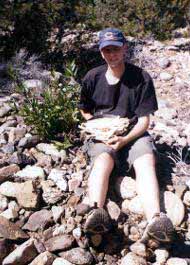

My companion on this expedition is Richard, a tall and lean eighteen year-old from Phoenix. Although new to the primitive camping experience, Richard is well read, conscientious of sustainable living issues, goal-oriented, and attitudally mature for his age. I needed a good walk-about to energize me before starting my fall project list at home, and Richard came along for a hands-on experience learning stone-age skills. I'm not sure he was quite prepared for the intensity of the experience, but he proved to be very adaptable on the trail. Actually, he told me later that he was sure he would die out there, but that was just because he watched too many movies about people getting killed in the woods.

The premise of our trip was simple. We would spend two days exploring the swamps, then hike back over the Tobacco Root Mountains to Pony. The distance is only twenty-four miles according to the ruler on the map, but we would have to scale or circumvent the mountain peaks in between. We probably walked closer to forty miles when all the loops back-and-forth on the trails are counted.

September should be the beginning of fall, but now the sun baked the land with an intensity unusual even for mid-summer. We waded into the swamps and spent most of our first day, Tuesday, in the water, exploring, eating cattail roots, and just enjoying being out. Good campsites are rare in the dredge piles, but we did locate a new sand bar and moved our gear there. We worked together to make a bowdrill fire set. I started the first fire, and Richard practiced and started the rest of our fires through the week. We brought no blankets, but instead we scraped away the sand, heated the ground with fire, then pushed back the sand and slept on the hot ground. We harvested last year's dried cattail stalks for a blanket over the top of us. My half of the bed was a little too hot. Richard's half was a little too cool.

September should be the beginning of fall, but now the sun baked the land with an intensity unusual even for mid-summer. We waded into the swamps and spent most of our first day, Tuesday, in the water, exploring, eating cattail roots, and just enjoying being out. Good campsites are rare in the dredge piles, but we did locate a new sand bar and moved our gear there. We worked together to make a bowdrill fire set. I started the first fire, and Richard practiced and started the rest of our fires through the week. We brought no blankets, but instead we scraped away the sand, heated the ground with fire, then pushed back the sand and slept on the hot ground. We harvested last year's dried cattail stalks for a blanket over the top of us. My half of the bed was a little too hot. Richard's half was a little too cool.

We brought basic food staples with us, like rice and lentils, bullion, oatmeal, flour, venison jerky and trail mix. However, I underestimated the amount of food we would need by at least a day. I'm not sure whether this was purely accidental, or if I subconsciously undercut the food supply so we would have to forage more along the way. Nevertheless, we ate fine all week. On Wednesday, our second day, we gathered a quantity of cattail roots for flour. I like to bring a small gold pan for cooking. With the aid of some vegetable oil, we stir-fried a delicious lunch of cattail buds and sow thistle leaves. The currants, gooseberries, and raspberries were few and far between, but we ate all we could find on the dry, half-brown bushes. We experimented with harvesting ants, but only came up with a couple teaspoons worth to add to a stew. We ate lots of rosehips.

By Thursday morning it was time for us to begin the trek back to Pony. We rose early, put our packs together and started walking, not even taking time to eat breakfast. Our packs were simple A-shaped frames made from willows, with buckskin thongs to tie the load on and shoulder straps to fit them to our backs. Richard made a copy of my packframe the day before the trip began.

The one item I wished we brought with us was a little sugar to work with the especially tart berries. As we walked up Granite Creek we found bushes loaded with buffalo berries, plus a few good chokecherries. Both types of berries are highly astringent with tannic acid that tightens tissues and puckers the inside of the mouth. We ate the fruits heartily, and I do not ever remember having my mouth so puckered before. Sugar would have enabled us to make a delicious pie with the berries. Without the sugar we used very few of the berries we harvested and took with us. Pounding and drying the berries would have helped too, but we didn't have time for that.

Farther up Granite Creek we took time to sit and watch a young bear in the road pulling over a chokecherry bush and stripping the cherries from it. The bear was not quite full grown, but it was on it's own. Mostly it bent the tree to the ground to eat, but for a moment it stood straight up on it's hind legs to reach up to the cherries. We sat in the road and watched until it either smelled or heard us and left.

Earlier this year Richard took a tracking class with Jim Halfpenny, author of Mammal Tracking in North America. I haven't focused much on tracking since high-school, but we both had fun looking at tracks and scat everywhere we went. Richard spotted a hole in one rock out-cropping that appeared to be a bobcat den. The round and narrow hole went straight back about ten feet into the rock.

We turned off Granite Creek at Mill Gulch and followed it high into the mountains. Grasshoppers big and small scattered before us as we walked. We caught more than a hundred for our dinner. In previous culinary experiences I found them to be bitter and unappetizing, but grasshopper cuisine is something I am determined to learn. We stir-fried the hoppers with buffalo berries and watercress, and although the bad taste was gone, we were unable establish a positive taste either. I thought the lemony-sour taste of the buffalo berries might help, but that was the worst part. I think next time just plain stir-fried grasshoppers with lots of watercress added at the last minute would be much better. Richard ate about half a dozen of them. I ate about two dozen. We disposed of the rest of the meal and cooked ashcakes instead.

We camped in the upper reaches of California Creek, probably about 8,000 feet in elevation. There was not enough insulating material in the mountains to make a good blanket, so we just slept by the fire all night. We rigged our ponchos as reflectors to bounce the heat to our backsides. The fire danger seemed high everywhere we went, and we did not know that all fires were banned because of the dry conditions, but we located our camp in a large patch of nearly barren ground. We kept our fire small.

The challenge in crossing the Tobacco Root Mountains is that we were traveling across most of the drainages, rather than with them. We could walk straight with lots of ups and downs, or follow the contour of the land and add lots of extra miles wrapping in and out of each drainage. We strived for a balance of both. Our total distance on Friday was relatively short, only about five miles straight, but it took us all day long to traverse the drainages along the way.

At one point in the day we rested near the ridge of the mountain, enjoying a lunch of ashcakes, water, and raw pine nuts. Suddenly a cow elk came around the side of the hill, walked no more than twenty feet in front of us and casually passed on by. I am sure that it smelled our trail. And although we tried to hold very still, with mouths full of ashcakes, I don't think we were really fooling anyone. The brief, but close encounter seemed like a real gift. We saw several more elk in the area as well.

One of the reasons I like to do these expeditions is to explore the area resources. This time we discovered whitebark pine nuts. I've heard about the natives collecting pine nuts in Montana before and some people still collect them today. But I've never been in the right place at the right time to harvest a good quantity of them, mostly because there are so few on our side of the mountains. However, this trek took us across the other side, to the West slope of the mountains, into an abundance of pine nuts. The cones we saw were high in the trees, but Richard found a squirrel cache with plenty of pine cones inside. Actually a bear found the cache first and ripped the old log apart, but there was still more than enough cones left for us. We ate some pine nuts on the spot and carried half a grocery bag of cones with us to camp. Bear piles marked the trails every where we went. We made camp near the Branham Lakes. We warmed and dried the cones by the fire through the night, then picked out the nuts on Saturday morning.

One of the reasons I like to do these expeditions is to explore the area resources. This time we discovered whitebark pine nuts. I've heard about the natives collecting pine nuts in Montana before and some people still collect them today. But I've never been in the right place at the right time to harvest a good quantity of them, mostly because there are so few on our side of the mountains. However, this trek took us across the other side, to the West slope of the mountains, into an abundance of pine nuts. The cones we saw were high in the trees, but Richard found a squirrel cache with plenty of pine cones inside. Actually a bear found the cache first and ripped the old log apart, but there was still more than enough cones left for us. We ate some pine nuts on the spot and carried half a grocery bag of cones with us to camp. Bear piles marked the trails every where we went. We made camp near the Branham Lakes. We warmed and dried the cones by the fire through the night, then picked out the nuts on Saturday morning.

The Paiute Indians roasted pinion pine nuts to make them more brittle. Then they used a stone to gently break the shells so they could be winnowed out from the nut meat. We roasted the pine nuts in my gold pan and attempted cracking and winnowing out the shells, but our success rate was very low. Either our roasting or cracking technique was inadequate, or possibly the whitebark pine nuts are just inherently more difficult to process than pinion pine nuts. In any case, the pine nuts were delicious shells and all, so that is how we ate them. There are not many wild plant foods in the west that provide true sustenance, but pine nuts are packed with energy.

We quickly sprinted to near the top of a 9600 foot pass, up until Richard got altitude sickness and had to stop and concentrate on breathing. But we did make it up and crossed over to the east slope of the mountains.

By the time we descended to Bell Lake the sky was partly cloudy, breezy and a little bit cool. We thought we might freeze in the mountain water, but we both needed the bath and our pants needed washing too, so we jumped right in, much to the amusement of a couple picnicking nearby. Yet the water was surprisingly warm and even the breeze felt good afterwards. We hiked down the trail a couple miles into the Potosi drainage before making camp.

Potosi is a favorite camping area for many people, and on holidays the canyon becomes an ATV race track. Our trail would take us miles down the canyon, but in order to avoid the mayhem we first slept for a few hours, then ventured out in the moonlight sometime after midnight. The night was cloudy, yet the full moon lit up the ground, even in the forest. We walked down the main road past all the tents and campers to Potosi hot springs. The hot pool is small, with room for only four to six people, but it is just exactly the right temperature-especially after many miles of hiking. The hot springs is very well known, so there are people in it pretty much all day long on the weekends. But we had no competition in the middle of the night. Our only company was the fire-flies, and they were nearly burned out for the night. We soaked for most of an hour, then put our packs back on for the last leg of the journey.

Hollowtop is the next drainage over from Potosi, but I always forget how much distance there is between the two. The trail starts with a steep, winding climb up out of Potosi. Richard led the charge up the hill, and I had trouble keeping up. We climbed a thousand vertical feet at a fast pace with only a couple thirty-second breaks for water. It occurred to me as I puffed along behind, that besides being goal-oriented, Richard was also a goal-achiever. He will certainly achieve anything in life that he sets his mind to.

We crossed the big meadow in the moonlight, then lay down for a few minutes with our heads on our packs. We listened to the elk bugling in the forest. When dawn of Sunday morning finally came we were more than ten miles from where we "camped" the evening before. We ate a final breakfast of ashcakes and pine nuts, and hiked in the last five miles. On the road back to Pony we found a garter snake that had just been run over. The tire track went right across it's middle, so it was writhing in agony. I smashed its head in with a rock to end the misery. The strange thing was that there were baby garter snakes inside, partly squished out of the wound. I thought that snakes always laid eggs, but I later learned that a few species, like garter snakes, give birth to live young.

Soon we arrived home, cleaned up, and officially ended our expedition with a great big dinner at the School House Cafe in Norris.

Go to Participating in Nature: Wilderness Survival and Primitive Living Skills

Return to the Primitive Living Skills Page

Primitive Living Skills

Primitive Living Skills

September should be the beginning of fall, but now the sun baked the land with an intensity unusual even for mid-summer. We waded into the swamps and spent most of our first day, Tuesday, in the water, exploring, eating cattail roots, and just enjoying being out. Good campsites are rare in the dredge piles, but we did locate a new sand bar and moved our gear there. We worked together to make a bowdrill fire set. I started the first fire, and Richard practiced and started the rest of our fires through the week. We brought no blankets, but instead we scraped away the sand, heated the ground with fire, then pushed back the sand and slept on the hot ground. We harvested last year's dried cattail stalks for a blanket over the top of us. My half of the bed was a little too hot. Richard's half was a little too cool.

September should be the beginning of fall, but now the sun baked the land with an intensity unusual even for mid-summer. We waded into the swamps and spent most of our first day, Tuesday, in the water, exploring, eating cattail roots, and just enjoying being out. Good campsites are rare in the dredge piles, but we did locate a new sand bar and moved our gear there. We worked together to make a bowdrill fire set. I started the first fire, and Richard practiced and started the rest of our fires through the week. We brought no blankets, but instead we scraped away the sand, heated the ground with fire, then pushed back the sand and slept on the hot ground. We harvested last year's dried cattail stalks for a blanket over the top of us. My half of the bed was a little too hot. Richard's half was a little too cool.  One of the reasons I like to do these expeditions is to explore the area resources. This time we discovered whitebark pine nuts. I've heard about the natives collecting pine nuts in Montana before and some people still collect them today. But I've never been in the right place at the right time to harvest a good quantity of them, mostly because there are so few on our side of the mountains. However, this trek took us across the other side, to the West slope of the mountains, into an abundance of pine nuts. The cones we saw were high in the trees, but Richard found a squirrel cache with plenty of pine cones inside. Actually a bear found the cache first and ripped the old log apart, but there was still more than enough cones left for us. We ate some pine nuts on the spot and carried half a grocery bag of cones with us to camp. Bear piles marked the trails every where we went. We made camp near the Branham Lakes. We warmed and dried the cones by the fire through the night, then picked out the nuts on Saturday morning.

One of the reasons I like to do these expeditions is to explore the area resources. This time we discovered whitebark pine nuts. I've heard about the natives collecting pine nuts in Montana before and some people still collect them today. But I've never been in the right place at the right time to harvest a good quantity of them, mostly because there are so few on our side of the mountains. However, this trek took us across the other side, to the West slope of the mountains, into an abundance of pine nuts. The cones we saw were high in the trees, but Richard found a squirrel cache with plenty of pine cones inside. Actually a bear found the cache first and ripped the old log apart, but there was still more than enough cones left for us. We ate some pine nuts on the spot and carried half a grocery bag of cones with us to camp. Bear piles marked the trails every where we went. We made camp near the Branham Lakes. We warmed and dried the cones by the fire through the night, then picked out the nuts on Saturday morning.