Tom's Camping Journal

The Tobacco Roots Trek II

Backbone of the Mountains

Tuesday September 28 - Saturday October 2, 1999

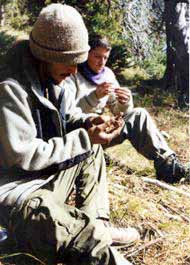

We sat on the hillside welcoming the warmth of the morning sun, peeling back the scales of the pine cones and popping pine nuts in our mouths. We competed with the bears and the squirrels and the Clark's nutcrackers for the tasty nuts, but we took no one's meal. There were acres and acres of pine nuts, more than all of us together could ever eat. It is the mother lode of wild edible plants-nutritious, tasty, and super-abundant--at least as if you are in the right place and the right time.

The whitebark pine starts at about 8000 feet in these mountains. The other pines and firs have edible seeds too, but only the whitebark pine is readily harvestable, starting in early to mid September in this region. Here the squirrels have clipped the cones from the upper reaches of the trees, littering the ground with thousands of cones. Like a man who has found a field of gold, the squirrels seemed to have gone mad, shuffling the pine cones from place to place, stacking some here, burying one there, caching some in holes under logs, picking up one pine cone only to put it down and run to the next.

The whitebark pine starts at about 8000 feet in these mountains. The other pines and firs have edible seeds too, but only the whitebark pine is readily harvestable, starting in early to mid September in this region. Here the squirrels have clipped the cones from the upper reaches of the trees, littering the ground with thousands of cones. Like a man who has found a field of gold, the squirrels seemed to have gone mad, shuffling the pine cones from place to place, stacking some here, burying one there, caching some in holes under logs, picking up one pine cone only to put it down and run to the next.

The ground was littered with bear piles too, clearly packed with hundreds if not thousands of pine nut shells in every pile as the animals stuffed themselves with the oil-rich food, putting on layers of fat for winter hibernation. We crossed paths with one bear on our way into camp last night, and found another just beyond our shelter this morning.

I felt like we were squirrels too, stuffing ourselves with pine nuts. We ate as many as we could, then quickly filled two big bags with pine cones to take back to camp, but there were so many more. Like the squirrels, I wanted them, I wanted them all!

The premise of this trip was to take advantage of the key crops of the season, to forage while the eating was good, then to walk back over the mountains towards home. We started down in the valley, in the swamps where there are acres and acres of cattails with starchy, abundant roots. We harvested more than enough roots for the journey home, plus rosehips and dried, shriveled gooseberries, before starting the walk into the mountains.

The adventure was originally intended to be a week long, but we shortened the beginning to better accommodate each of our schedules. Even then, Steven and I were in the field for almost twenty-four hours before David caught up with us. He had been trapped in another range of mountains by a sudden snow storm, and couldn't drive out until the snow melted. He stopped by the house and got directions to find us in the swamps on the other side of the mountains.

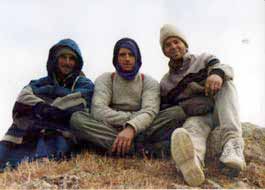

Both Steven and David were experienced travelers. Steven, thirty-seven, came the night before the expedition, after driving in from North Carolina. He was an experienced backpacker and traveler. He has backpacked the Appalachian Trail, plus many areas of the west, in addition to traveling and living abroad. He was used to carrying a sixty-pound backpack. He came on this trip to learn how to travel lightly, leaving the tent and sleeping bag behind, and how to forage for wild food. He made a Roycroft-style packframe at the house on the morning our adventure began.

Both Steven and David were experienced travelers. Steven, thirty-seven, came the night before the expedition, after driving in from North Carolina. He was an experienced backpacker and traveler. He has backpacked the Appalachian Trail, plus many areas of the west, in addition to traveling and living abroad. He was used to carrying a sixty-pound backpack. He came on this trip to learn how to travel lightly, leaving the tent and sleeping bag behind, and how to forage for wild food. He made a Roycroft-style packframe at the house on the morning our adventure began.

David, twenty-six, was from California. Like Steven, he has traveled and lived abroad, learning foreign languages and experiencing other cultures. This year he has taken primitive skills classes at several schools in the west. But backpacking across the mountains with no trails was a new experience, he said. He started a Roycroft-style packframe at Rabbitstick Rendezvous in Idaho the week before the trip, then finished it after he found us in the swamps.

Our first campsite was at a favorite spot in the swamps. There was a hut at this camp, which I built with a group back in August, but now there was two inches of water in it. I knew there would be water there at least part of the year, but didn't expect it until spring. We built the hut there only because it was completely invisible. It was no great loss with the water in it. Steven and I just pulled the dried cattail and sedge leaves off the hut and used them to make an insulating blanket over our hot coal beds nearby.

We dug a shallow trench for the beds and started a fire with flint & steel, then collected cattail roots from the swamp to supplement our rations. Steven shared this entry from his journal:

We dug a shallow trench for the beds and started a fire with flint & steel, then collected cattail roots from the swamp to supplement our rations. Steven shared this entry from his journal:

"We shed our pants and boots and stepped into the frigid water and slowly walked through the calf-deep silky mud feeling with our feet for the horizontal roots of the cattails. When we found one we'd stick our hands deep into the mud and slowly pluck the root from its moorings. We did this for a while until we'd gathered quite a few and then took them over to another area of the creek to wash them in running water. Later, we cooked some over the fire. I found them easily palatable. We would peel off the sides and stick the middle of the root into our mouths chewing up the starchy strands (which to me tasted a little like potatoes) and spit out the fibers. The provided a good addition to dinner."

One thing I learned this year is that the bland, starchy cattail roots are much more palatable if you combine them with berries or some other kind of tasty food for flavor. We cooked the cattail roots on the coals, then ate them with rosehips. For our first dinner we ate rice and lentils plus goat jerky I made a couple weeks before. It was edible, but definitely not first-class faire. The rosehip tea was the highlight of the evening.

Our fire warmed the ground until dark while the air around us grew colder and colder. Finally we covered the fire with dirt, a poncho, and a big pile of cattail insulation. The loose cattail stalks allowed air to infiltrate through, so we put our other poncho over the insulation to block out the cold air. Then we wriggled underneath the insulation. The warm ground beneath us felt nice, but unfortunately both the coal bed and the poncho over the insulation were a little short. We were perfectly warm except for our frozen feet! In the middle of the night we took the poncho out from underneath us and put it up top, to help block the cold air, then weighted it down with sticks and rocks. That made the bed a lot more tolerable, but still we went though the night with little sleep. Sometimes it takes a couple nights to fine-tune a shelter. Steven was very enthusiastic for the skills, but unfortunately, a night without sleep gave him a horrible headache. He took several naps during the day.

I half-feared that Steven and David might bail on me, like my group did in August, when they were not quite as comfortable as they expected to be. That was my fault really; I should have warned them that it would not be easy. People often get into primitive skills with the romantic notion that you can go out and live in bliss and harmony with nature. They don't realize that on the path to harmony you have to morph into a half-wild creature that loves heat and cold and wet and strange foods and weird sleep. This time I warned all the interested parties before the trip, yet Steven and David were still eager to go.

Steven wrote: "In the afternoon David and I practiced starting fires with a bow and drill while Tom went over to the edge of the stream to prepare food for dinner. That evening we had a tasty stir-fry of cattail shoots, mustard greens, and duckweed along with ashcakes (wheat flour with grass seed and poppy seed made into cakes and thrown into the ashes to cook) and rose hip tea. The meal was more than satisfying and not long after eating I became exhausted and was ready to collapse due to lack of sleep. David made an additional coal bed, and Tom and I extended ours so our feet wouldn't be sacrificed during the night. But it turned out that the night was warmer than the previous one and after a few hours I found myself deburrowing. I had to get out and shed some clothing to dry and cool off. The few modifications we made to the coal bed proved overly sufficient. Eventually I laid back down for a short sleep."

Steven wrote: "In the afternoon David and I practiced starting fires with a bow and drill while Tom went over to the edge of the stream to prepare food for dinner. That evening we had a tasty stir-fry of cattail shoots, mustard greens, and duckweed along with ashcakes (wheat flour with grass seed and poppy seed made into cakes and thrown into the ashes to cook) and rose hip tea. The meal was more than satisfying and not long after eating I became exhausted and was ready to collapse due to lack of sleep. David made an additional coal bed, and Tom and I extended ours so our feet wouldn't be sacrificed during the night. But it turned out that the night was warmer than the previous one and after a few hours I found myself deburrowing. I had to get out and shed some clothing to dry and cool off. The few modifications we made to the coal bed proved overly sufficient. Eventually I laid back down for a short sleep."

Our night was short, but not because it was cold. We were all on our feet by three o'clock in the morning to start hiking up into the mountains. David was behind on his sleep too, from staying up nights for the last week. But we packed our gear, cleaned up camp, and ventured forth into the moonlight. The night was remarkably warm and beautiful.

The reasons for traveling at night were several. First, there is a certain ambiance to walking in the moonlight. The distant noises of civilization fade away, leaving behind a very quiet place-the seeming reemergence of the ancient world from which we all came. The moonlight is a gentle light, not at all glaring like in the day time. I love to walk and watch the clouds pass by the moon, taking us from moonlight to near darkness and back again.

The reasons for traveling at night were several. First, there is a certain ambiance to walking in the moonlight. The distant noises of civilization fade away, leaving behind a very quiet place-the seeming reemergence of the ancient world from which we all came. The moonlight is a gentle light, not at all glaring like in the day time. I love to walk and watch the clouds pass by the moon, taking us from moonlight to near darkness and back again.

We moved at night also because our path took us across roads and farms on our way into the mountains. It was nice to pass by invisibly, like the many other creatures of the wild that come out to play when humans disappear into their holes. It was a peaceful and uneventful walk. We searched in vain for berries, but harvested some watercress along the way. Eventually the bright light of Venus emerged atop the crest of the hill, and we knew daylight was close behind. The night grew colder and colder right up until dawn. By first light we were ready for a break and some sleep. We laid down in the shelter of the junipers and took a short nap. We awoke probably twenty minutes later, and already it was fully light out. We shouldered our packs and set forth deeper into the mountains.

The other reason we started our journey at night was because we had a long ways to go to get up to the pine nuts, and fall days are just too short. Starting early in the day allowed us to move through the mountains at a leisurely pace. We had time to stop and talk about wild plants, to watch the wildlife, and to take naps in the sun.

From Steven's journal: "We hiked about ten miles that day from lower desert terrain to higher forests filled with spruce, pine, aspen and fir. Along the way we found foods such as the seeds from various mustard plants which were delicious. We ate two varieties of rose hips, more gooseberries, and harvested watercress from a stream to be eaten later. We also munched on leftover ashcakes and buffalo berries. Everywhere we hiked we found water, usually in strong, flowing streams. As we slowly climbed through a sunlit, grassy valley we shared the slopes with moose and deer. We discovered more edibles and healing plants such as Shepherd's Purse and yarrow and then dozed in tall grass on a hillside after lunch. Each day we would come across a new plant, root or weed of which Tom would disclose information on various characteristics and tell us whether or not each was edible or contained medicinal value. His approach to teaching was effectively random and unconventional. Not so much like teaching, but as we moved through the days it was like walking through a continuous open-air classroom where "lessons" in the form of plants, animals, and elements would pop up and present themselves for discussion regularly. It was like walking through an abstract painting where all the elements that make it up, slowly take shape, so when you step out of it the full picture becomes obvious. Yet before we went in, it was just a jumble of attractive colors."

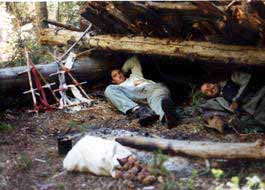

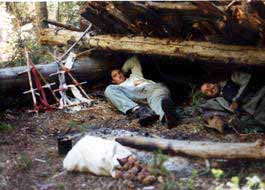

By the end of the day we had climbed from 5600 feet in elevation up to 8000 feet. We made camp as the patchy clouds began to spit out raindrops and sometimes snowflakes. Shelter was definitely not a problem with so much rotten wood on the ground. The trees gave us adequate cover to start with anyway, so David started the fire with the bowdrill, and we cooked noodles and split-pea soup for dinner, thankful to have some instant foods with us. Later we constructed a lean-to long enough for Steven and I to sleep by the fire with our legs over-lapping in the middle. David slept in the back of the shelter with his blanket. The night was relatively warm with the cloud cover overhead. We slept well in fits and spurts, in between sessions of loading wood on the fire. We feared that the clouds might turn to snow over night, but instead they simply blew away, leaving us with a clear and beautiful, but cool day for our pine nut harvest.

By the end of the day we had climbed from 5600 feet in elevation up to 8000 feet. We made camp as the patchy clouds began to spit out raindrops and sometimes snowflakes. Shelter was definitely not a problem with so much rotten wood on the ground. The trees gave us adequate cover to start with anyway, so David started the fire with the bowdrill, and we cooked noodles and split-pea soup for dinner, thankful to have some instant foods with us. Later we constructed a lean-to long enough for Steven and I to sleep by the fire with our legs over-lapping in the middle. David slept in the back of the shelter with his blanket. The night was relatively warm with the cloud cover overhead. We slept well in fits and spurts, in between sessions of loading wood on the fire. We feared that the clouds might turn to snow over night, but instead they simply blew away, leaving us with a clear and beautiful, but cool day for our pine nut harvest.

In addition to gathering pine nuts in the morning sun, we took some time for plant identification skills, and we collected wild tarragon and biscuit root seeds to flavor our ashcakes. Steven wrote:

"Hours are required to pluck the pine nuts from the cones through the unavoidable pitch, making it a very sticky task. David took to it well and plucked so many pine nuts that we could have been fed three times over and still had enough to roast up as a peace offering for the squirrels."

The nuts were delicious raw, but heavenly when roasted. I set up a metate stone and processed some to remove as many shells as possible, then we added the nuts and wild seasonings to our ashcake mix, along with grass seed and plantain seed brought from home. We cooked and ate several small meals of rice and lentils during the day too. We ate some of the ashcakes with dinner, and saved the rest for trail food.

By late afternoon the sky was crystal clear and the night threatened to be very cold. We tightened the debris cover on the lean-to, then quickly built two more log walls around the campfire to help capture and reflect the heat. This time we all slept close to the fire. But night was not as cold as we feared, and we awoke to another perfect day.

The weather at this time of year can be difficult to predict. On this trip the sky changed constantly from clear to wispy to cloudy and back again, as successive fronts swept quickly by. We were ill-equipped for snow, and we planned to abort the mission over the mountains if the weather turned bad, but we were very lucky again that day. We ate cattail roots and ashcakes for breakfast, then tore down and dispersed the shelter before heading out.

I'd been toying with the idea of walking the backbone of the mountains for some time. If we climbed up to an elevation of 9,000 or 10,000 feet, then we would only have to walk a few miles along the ridge to put us across most of the Tobacco Roots Mountains, and virtually all the way home. Besides being spectacular, it would save two or three days of hiking up and down the watersheds to either side. I mentioned something about soaking in a hot pot up Potosi canyon on the other side, and taking the guys out to dinner afterwards, and they practically sprinted over the mountains. I intended to camp somewhere after the peaks before the hot springs, but they wanted to do it all in one day. I didn't realize that it was supposed to be the last day of our journey anyway, until we got home and looked at the calendar.

Hiking at high elevations is usually difficult for me the first time each year, but this time it seemed easy. On the way up I picked up one pine cone after another, and popped the tasty nuts into my mouth as we walked. I felt this incredible surge of energy all day, as if I was running on pure pine nut power!

Hiking at high elevations is usually difficult for me the first time each year, but this time it seemed easy. On the way up I picked up one pine cone after another, and popped the tasty nuts into my mouth as we walked. I felt this incredible surge of energy all day, as if I was running on pure pine nut power!

I'm not sure quite how Steve and David walked up the mountains without eating so much as I did, but they said they were motivated by that hot springs on the other side. Every break we took was short. The high elevations were especially hard for David, but he kept charging along anyway.

Steven wrote: "As we moved through the forest, the honk and squeal of an elk slipped through the trees from an unseen distance. We heard the wings of Clark's nutcrackers and crows overhead audibly whirring like machines of brushing wind. We were blessed with another blue day, at least at that elevation. As we climbed higher the trees began to thin out and patches of snow became evident. When the start of the ridge was in full view we stopped for a food break and added a layer or two of clothing. The temperature was already dropping and the sky was turning slate gray as we prepared for a final waltz with the metaphysical. We kept our eyes open for more big animals and watched as the fog bank crept up through the lower mountains like an encroaching specter with nothing but time on its hands. It seemed as if it would eventually overtake us."

We could see first into the Madison Valley, where the thick blanket of fog filled the canyon between the mountains. We watched as the fog lifted higher and higher, but it never dissipated. To the west the Ruby Valley was clear of fog, but hazy. We skirted around the peak of Ramshorn Mountain and found ourselves looking down on South Meadow Creek Lake, like a fairy tale scene with an endless blanket of fog covering the valley beyond it.

Steven wrote: "Our first hour on the ridge was spent stepping cautiously across a seemingly endless field of rocks on a slope angled at about forty-five degrees. We were now above the tree line and the view of the rest of the world below was expanding. Some time after we'd cleared the rock field we realized a slight miscalculation with the topographic map and had to backtrack a little on to another ridge line. This took us along a grassy slope for some time and the views of the green-blue alpine tarns below were magnificent. These pale, yellow balds were a wind-ravaged, indifferent terrain. The kind of place that sticks your individual insignificance in your face and reminds you of your constant vulnerability. Conversely though, it's infectiously reassuring of the here-and-now."

I often bring my camera, but usually leave it deep inside my pack. I rarely stop and take the time to get it out. But today I chose to wear the camera on my neck all day long. I shot up an entire roll of film of the peaks and lakes and the fog along the way. I think David and Steven had more than enough of my picture taking by the end of the day!

As the day continued we passed by Porphyry Mountain and looked down into Lupine Lake, Lilly Lake, Cliff Lake, and Alpine Lake. (Check out this MAP!) The terrain across the top varied from rocky and talus slopes to thick, lush carpets of dried alpine vegetation. Two young bull moose sat on the ridge at 9,800 feet, seeming to enjoy the scenery as much as we were. We were sorry to disturb them in their moment of quietude upon their temple, but they did slowly get up and leave when we passed by. I took their picture anyway, from a distance.

"The few times I'd seen moose, they were always among trees. My vision of moose had always comprised of a forest setting and a cautious vigilance against grizzlies and now here were two young bulls high in the saddle of this ridge, sitting long on the ground, their heads up and casually looking about from a timeless perch, on the world below them which at that time they seemed in command of. Their concerns had nothing to do with the cold or the biting wind or even the threatening sky. They knew nothing of borders, of the paradox of governments or the absurdity of land-ownership. They were completely in tune with all that was around them--their senses fully honed and everything in their world, true and deliberate. The only sound up there was the determined wind rushing across the slope. Occasionally these winds would subside and then a burst of quiet grafted into the dimension of the atmosphere and we were as good as prehistoric man."

"As we continued on toward that next peak, passing the moose, we stayed a reasonable distance below them in hope of not disturbing them. They watched us a while and then slowly started for lower ground, exchanging glances with us from time to time. The image of these moose, easy above the world, quickly became an eternal reference for me, epitomizing the power of harmony."

From the peaks we could see that the Gallatin Valley was also fogged in--a fluffy white blanket extending sixty miles across between the mountains. We could see the tips of the Bridger peaks on the other side, like a chain of islands in a white sea. By now the sky above us was partly cloudy , a mix of wispy clouds and thicker cumulus, white but sometimes gray, occasionally spitting out a few white flakes. We seemed to be in a cloud sandwich with clouds above us and below, but none in our space where we walked. I took lots more pictures. As Steven kept saying over and over, "What an incredible way to end this kind of a trip!"

From the peaks we could see that the Gallatin Valley was also fogged in--a fluffy white blanket extending sixty miles across between the mountains. We could see the tips of the Bridger peaks on the other side, like a chain of islands in a white sea. By now the sky above us was partly cloudy , a mix of wispy clouds and thicker cumulus, white but sometimes gray, occasionally spitting out a few white flakes. We seemed to be in a cloud sandwich with clouds above us and below, but none in our space where we walked. I took lots more pictures. As Steven kept saying over and over, "What an incredible way to end this kind of a trip!"

We looked down over the Twin Lakes and the Branham Lakes as we continued to work our way along the ridge, over and around the peaks past Lady of the Lake Peak to the saddle by Mount Bradley.

Steven wrote: "We studied this last peak, characterized by massive gray concave walls of loose rocks and boulders which had been formed and situated by glacial activity and erosion through time immemorial. Among these rocks were rounded indentions of permanent snow and ice. These spoon-shaped talus walls rose hundreds of feet to form the peak at the top and now we were discussing the idea of slipping into one of the steep breaks in the wall and traversing yet another field of rocks. However, this field bent at an angle of about sixty degrees and a poorly placed foot might easily turn into a rapid and bumpy ride to the bottom of which very few people would survive. But it was too enticing and meant that we wouldn't have to climb any higher, so we proceeded judiciously. As we picked our way across this wall, a lone mountain goat, hundreds of feet below us, foraged on a rise. In less than an hour we were on the other side."

We felt like mountain goats ourselves, traversing that rocky hillside. But, finally we began our descent into the Potosi drainage. The trip down seemed to last forever. It was not excessively steep, but just went on and on, as we navigated back and forth across the creeks and around the obstacle course of fallen trees. It was nearly dark when we reached an established trail. It was definitely dark by the time we reached the road. There were still miles to go before we would reach the hot springs, and we would be too late at night to use a nearby telephone to call for our ride out. We debated what course of action to take as we tromped down the road. David was nearly ready to fall asleep. But then the lights of a truck appeared behind us. It may have been the only ride out that night. We stuck out our thumbs and hitched back to Pony. We ate dinner at the house and waited until the next morning to eat out and celebrate. It was in every way just the right kind of trip to end a summer of fun.

Go to Participating in Nature: Wilderness Survival and Primitive Living Skills

Return to the Primitive Living Skills Page

Primitive Living Skills

Primitive Living Skills

The whitebark pine starts at about 8000 feet in these mountains. The other pines and firs have edible seeds too, but only the whitebark pine is readily harvestable, starting in early to mid September in this region. Here the squirrels have clipped the cones from the upper reaches of the trees, littering the ground with thousands of cones. Like a man who has found a field of gold, the squirrels seemed to have gone mad, shuffling the pine cones from place to place, stacking some here, burying one there, caching some in holes under logs, picking up one pine cone only to put it down and run to the next.

The whitebark pine starts at about 8000 feet in these mountains. The other pines and firs have edible seeds too, but only the whitebark pine is readily harvestable, starting in early to mid September in this region. Here the squirrels have clipped the cones from the upper reaches of the trees, littering the ground with thousands of cones. Like a man who has found a field of gold, the squirrels seemed to have gone mad, shuffling the pine cones from place to place, stacking some here, burying one there, caching some in holes under logs, picking up one pine cone only to put it down and run to the next.  Both Steven and David were experienced travelers. Steven, thirty-seven, came the night before the expedition, after driving in from North Carolina. He was an experienced backpacker and traveler. He has backpacked the Appalachian Trail, plus many areas of the west, in addition to traveling and living abroad. He was used to carrying a sixty-pound backpack. He came on this trip to learn how to travel lightly, leaving the tent and sleeping bag behind, and how to forage for wild food. He made a Roycroft-style packframe at the house on the morning our adventure began.

Both Steven and David were experienced travelers. Steven, thirty-seven, came the night before the expedition, after driving in from North Carolina. He was an experienced backpacker and traveler. He has backpacked the Appalachian Trail, plus many areas of the west, in addition to traveling and living abroad. He was used to carrying a sixty-pound backpack. He came on this trip to learn how to travel lightly, leaving the tent and sleeping bag behind, and how to forage for wild food. He made a Roycroft-style packframe at the house on the morning our adventure began. We dug a shallow trench for the beds and started a fire with flint & steel, then collected cattail roots from the swamp to supplement our rations. Steven shared this entry from his journal:

We dug a shallow trench for the beds and started a fire with flint & steel, then collected cattail roots from the swamp to supplement our rations. Steven shared this entry from his journal:  Steven wrote: "In the afternoon David and I practiced starting fires with a bow and drill while Tom went over to the edge of the stream to prepare food for dinner. That evening we had a tasty stir-fry of cattail shoots, mustard greens, and duckweed along with ashcakes (wheat flour with grass seed and poppy seed made into cakes and thrown into the ashes to cook) and rose hip tea. The meal was more than satisfying and not long after eating I became exhausted and was ready to collapse due to lack of sleep. David made an additional coal bed, and Tom and I extended ours so our feet wouldn't be sacrificed during the night. But it turned out that the night was warmer than the previous one and after a few hours I found myself deburrowing. I had to get out and shed some clothing to dry and cool off. The few modifications we made to the coal bed proved overly sufficient. Eventually I laid back down for a short sleep."

Steven wrote: "In the afternoon David and I practiced starting fires with a bow and drill while Tom went over to the edge of the stream to prepare food for dinner. That evening we had a tasty stir-fry of cattail shoots, mustard greens, and duckweed along with ashcakes (wheat flour with grass seed and poppy seed made into cakes and thrown into the ashes to cook) and rose hip tea. The meal was more than satisfying and not long after eating I became exhausted and was ready to collapse due to lack of sleep. David made an additional coal bed, and Tom and I extended ours so our feet wouldn't be sacrificed during the night. But it turned out that the night was warmer than the previous one and after a few hours I found myself deburrowing. I had to get out and shed some clothing to dry and cool off. The few modifications we made to the coal bed proved overly sufficient. Eventually I laid back down for a short sleep." The reasons for traveling at night were several. First, there is a certain ambiance to walking in the moonlight. The distant noises of civilization fade away, leaving behind a very quiet place-the seeming reemergence of the ancient world from which we all came. The moonlight is a gentle light, not at all glaring like in the day time. I love to walk and watch the clouds pass by the moon, taking us from moonlight to near darkness and back again.

The reasons for traveling at night were several. First, there is a certain ambiance to walking in the moonlight. The distant noises of civilization fade away, leaving behind a very quiet place-the seeming reemergence of the ancient world from which we all came. The moonlight is a gentle light, not at all glaring like in the day time. I love to walk and watch the clouds pass by the moon, taking us from moonlight to near darkness and back again.  By the end of the day we had climbed from 5600 feet in elevation up to 8000 feet. We made camp as the patchy clouds began to spit out raindrops and sometimes snowflakes. Shelter was definitely not a problem with so much rotten wood on the ground. The trees gave us adequate cover to start with anyway, so David started the fire with the bowdrill, and we cooked noodles and split-pea soup for dinner, thankful to have some instant foods with us. Later we constructed a lean-to long enough for Steven and I to sleep by the fire with our legs over-lapping in the middle. David slept in the back of the shelter with his blanket. The night was relatively warm with the cloud cover overhead. We slept well in fits and spurts, in between sessions of loading wood on the fire. We feared that the clouds might turn to snow over night, but instead they simply blew away, leaving us with a clear and beautiful, but cool day for our pine nut harvest.

By the end of the day we had climbed from 5600 feet in elevation up to 8000 feet. We made camp as the patchy clouds began to spit out raindrops and sometimes snowflakes. Shelter was definitely not a problem with so much rotten wood on the ground. The trees gave us adequate cover to start with anyway, so David started the fire with the bowdrill, and we cooked noodles and split-pea soup for dinner, thankful to have some instant foods with us. Later we constructed a lean-to long enough for Steven and I to sleep by the fire with our legs over-lapping in the middle. David slept in the back of the shelter with his blanket. The night was relatively warm with the cloud cover overhead. We slept well in fits and spurts, in between sessions of loading wood on the fire. We feared that the clouds might turn to snow over night, but instead they simply blew away, leaving us with a clear and beautiful, but cool day for our pine nut harvest. Hiking at high elevations is usually difficult for me the first time each year, but this time it seemed easy. On the way up I picked up one pine cone after another, and popped the tasty nuts into my mouth as we walked. I felt this incredible surge of energy all day, as if I was running on pure pine nut power!

Hiking at high elevations is usually difficult for me the first time each year, but this time it seemed easy. On the way up I picked up one pine cone after another, and popped the tasty nuts into my mouth as we walked. I felt this incredible surge of energy all day, as if I was running on pure pine nut power!  From the peaks we could see that the Gallatin Valley was also fogged in--a fluffy white blanket extending sixty miles across between the mountains. We could see the tips of the Bridger peaks on the other side, like a chain of islands in a white sea. By now the sky above us was partly cloudy , a mix of wispy clouds and thicker cumulus, white but sometimes gray, occasionally spitting out a few white flakes. We seemed to be in a cloud sandwich with clouds above us and below, but none in our space where we walked. I took lots more pictures. As Steven kept saying over and over, "What an incredible way to end this kind of a trip!"

From the peaks we could see that the Gallatin Valley was also fogged in--a fluffy white blanket extending sixty miles across between the mountains. We could see the tips of the Bridger peaks on the other side, like a chain of islands in a white sea. By now the sky above us was partly cloudy , a mix of wispy clouds and thicker cumulus, white but sometimes gray, occasionally spitting out a few white flakes. We seemed to be in a cloud sandwich with clouds above us and below, but none in our space where we walked. I took lots more pictures. As Steven kept saying over and over, "What an incredible way to end this kind of a trip!"